“Nā te Atua, te taonga (ngā mokopuna) hei ārahi i a tātou (the mokopuna is the gift from God, that guides us in their uniqueness)” – this is the phrase used by Denise Marshall, tumuaki of Te Kura Kaupapa Māori o Manawatū when asked for words to describe tamariki with different learning needs.

This Palmerston North kura has embraced such children from the time it was set up in 1990. “My daughter Waimarie was a child with spina bifida, in a wheelchair. She was the first child with a physical disability to attend kura kaupapa throughout the country, as far as we know. She brought her own uniqueness to help guide us.” The kura has also had children with cerebral palsy, Down syndrome, and behavioural and learning challenges.

“We are very much open and confident in bringing our children into the world that we perceive as unique for us. Ko te tamaiti te pūtake o te ao – the learning centres on the child and what they bring to the table. We look at the holistic nature of the child, and we grow with them.”

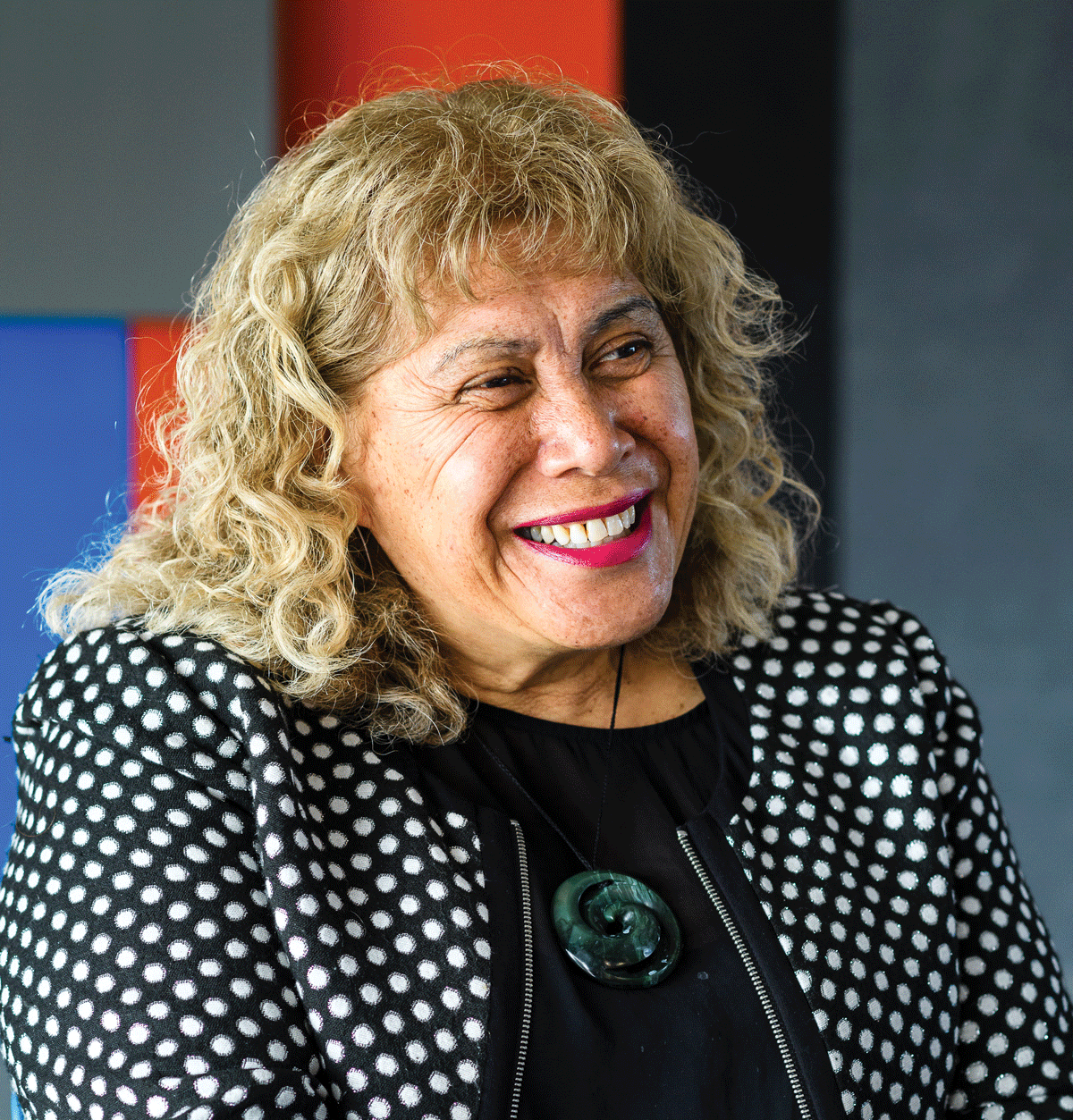

“Ko te tamaiti te pūtake o te ao – the learning centres on the child and what they bring to the table.”

Tumuaki of Te Kura Kaupapa Māori o Manawatū Denise Marshall

The purpose-built complex of buildings the kura now occupies was especially designed for children with special needs – with wheelchair ramps, wheelchair access pathways, and toilet and shower facilities for the disabled. “Everything’s accessible,” says Marshall. “I’ve been a very strong advocate, ensuring that the kura has that awareness for all our tamariki.”

Staff at the kura learn from whānau about how to teach and learn with their child with physical, behavioural or learning challenges. They also employ extra support staff when required.

“It’s actually changing the world of our staff and how they think – that a child belongs to all of us, it doesn’t belong to the teacher aide. It’s inclusive, we all need to support each other – child and whānau – to walk that pathway.”

Te Aho Matua, the guiding philosophy of kura kaupapa Māori, in its first section Te Ira Tangata, emphasises the need to nurture and care for each child in their uniqueness. It includes the whakataukī – Ahakoa he iti, he māpihi pounamu – referring to the singular beauty and immense value of even the tiniest piece of fine greenstone. Each child has spiritual qualities, including mauri, tapu and mana; and the development of the whole child is important. Te Aho Matua emphasises the creative arts, such as music and drama, and the importance of whānau and tuakana/teina supportive relationships.

“Our kapahaka group included, and still includes, all our children with special needs,” says Marshall. “You can feel their wairua, that confidence that they’re standing up and knowing that they belong and feel connected. They’re proud to wear that piupiu because they’re representing their kura.”

Everyone is also included in sports, if they choose to be. Waimarie played netball. Marshall says, “Everybody was taught to run sideways or use their peripheral vision so you knew where the wheelchair was. They’re proud to wear their uniform, whether it be sports, or standing on the sideline. You’re still wearing the uniform, because you’re connected. That’s inclusiveness.” Planning for school trips also includes all tamariki and their whānau, which helps staff and whānau to get to know one another.

But some of the challenges for Te Kura Kaupapa Māori o Manawatū are, and have always been, getting specialist support and extra putea or funding for extra support staff, and also for special learning resource materials.

“It took us a couple of years before we started getting any ORS (On-going Resourcing Scheme) funding,” says Marshall. “Probably because we wrote them in te reo Māori, and we didn’t think of our tamariki as deficits, so we would write to them on what they could do.” Marshall felt the emphasis should be on helping the child connect to the kura, rather than literacy and numeracy. “In the end we managed to find someone to come in and help us write to the requirements of that (application) and in English.” [ORS funding is for students with high needs, and provides for specialists, for example, physiotherapists, psychologists and also specialist teachers or teacher aides.]

And when specialists such as physiotherapists or speech therapists have arrived to help, they are usually unable to speak te reo Māori or understand te ao Māori. “I’d ask what they required, then I’d be doing the translation, talking to the child, at the same time as running a class next door,” says Marshall. “Language was a barrier, and culture was a barrier. We had to build relationships with them to help them understand. It worked because we had to make it work so that the child could learn and feel connected.”

The kura has regular visits from the local Resource Teacher of Learning and Behaviour Peter Te Rangi (Rangitāne), who has had a long-term relationship with the kura.

Sometimes it takes years for a child to settle in and learn to trust staff. Key components are aroha, patience and tolerance.

The kura is also advised by a parent, an educational psychologist who understands te reo and how the kura operates. Sometimes it takes years for a child to settle in and learn to trust staff. Key components are aroha, patience and tolerance, says pou-āwhina Nancy Keelan-Tibble. “Tiakina ngā mokopuna.”

Te Rangi says, “This kura has led the way. They’ve had children with a range of learning needs, and they’ve managed to work really well with all of them.”

Marshall says, “Our doors are always open, we welcome anyone and everyone who is committed to te reo Māori me te ao Māori. Ko te ahurei o te tamaiti ārahia o tātou mahi – let the uniqueness of the child guide us in our mahi.”

Lighting the flames of yearning and learning: a whole whānau approach

The most effective interventions for improving the engagement of tamariki with learning are those which build the ability of parents and other family members to support their child’s learning, as well as building teacher understanding of the resources within the local community, according to the Ministry of Education’s Best Evidence Synthesis data. [Robinson, V. Hohepa,M. & Lloyd, C. (2009) BES, University of Auckland, Ministry of Education.]

In the Horowhenua, a local iwi authority was able to take the lead, engage kaumatua and whānau, integrate cultural knowledge, and build positive relationships between whānau with the school, resulting in strong outcomes.

The Ministry of Education’s strategy Ka Hikitia promotes “Māori success as Māori”, and this was the focus of the programme led by Muaūpoko Tribal Authority with tamariki at Levin East Primary School, which began and ended at Kawiu Marae.

At its heart was Muaūpoko-tanga (traditional cultural knowledge of Muaūpoko), but it also included Reading Together, which supports parents, aunts, uncles and grandparents to read to and with their tamariki or mokopuna.

Muaūpoko Tribal Authority Chief Executive Di Rump worked in partnership with whānau, school board and management staff, the Ministry of Education and the JR McKenzie Trust to develop the programme. “Reading Together fitted within a bigger ‘Tungia te Koingo’ [lighting the flames of yearning and learning], named by one of our parents.

“It was based on Ka Hikitia, so we had the opportunity to do the ‘as Māori’ piece, as Muaūpoko. Tamariki learnt pepeha, visited pepeha and wrote stories about pepeha,” says Rump. The children also painted a mural on the wall at their school to represent what they had learnt.

The programme started after the Muaūpoko Tribal Authority approached the Ministry about accelerating achievement for Māori in Taitoko/Levin. Levin East School was also keen to have more input from iwi and whānau at the school, which has a high percentage of Māori children, many of them Muaūpoko. The involvement of Muaūpoko Tribal Authority board member Marokopa Wiremu-Matakatea, who has mokopuna at the school, was crucial because of his leadership and cultural knowledge.

Because Reading Together is patented and carefully managed, consent had to be sought and gained to modify it.

While Reading Together focuses on literacy (reading, writing and numeracy), the iwi decided to support this within a framework of their own tikanga and mātauranga. Because Reading Together is patented and carefully managed, consent had to be sought and gained to modify it.

An extra two weeks were added to the programme to allow for “Mana Monday” visits to Kawiu Marae and other sites of significance – maunga (Tararua), lakes Horowhenua and Waiwiri and the beach. Visits were also made to a donor business, Paper Plus, to choose literacy resources, and to a local library/museum Te Takeretanga o Kurahaupo. “Uncle spoke about some of the history of the artwork and taonga there,” says Rump.

Two buses were needed for these outings, as about 60 children and whānau, teachers and board members wanted to attend. The programme included breakfast clubs, attended by parents and teachers, where karakia and waiata were shared. New words were taught and meanings explained.

“Whenever we could, we injected Muaūpokotanga into it,” says Rump. “It was successful because of being within a wider context.” The programme included a bigger trip (haerenga) to Te Papa in Wellington, where more Muaūpoko taonga were seen, and every term a whānau hui was held. “What we provided was the kai and baby-sitters, those were the two key things,” says Rump.

Teacher Roni (Veronica) Sayer says, “We wanted to Muaūpoko-ify the programme, and we made sure we let whānau dictate where and how. It was great for building those relationships!”

“We wanted to Muaūpoko-ify the programme, and we made sure we let whānau dictate where and how. It was great for building those relationships!”

Teacher Roni (Veronica) Sayer

The confidence of the children has improved enormously, as their sense of belonging within their iwi as well as in their school has been strengthened, she says. “These guys have really stepped up, and learning has been on an upward trajectory ever since.”

Wiremu-Matakatea adds, “I think the key to this success was lighting the fire within the mokopuna, because without that, none of the other things would have happened.”

He had to consciously simplify his language for the children, and link the cultural knowledge to what they knew, for example, suggesting they give their favourite teacher a tupuna name. As a result they were able to grasp early ancestral knowledge, such as, that Whatonga came to Aotearoa on the Kurahaupo waka and later came to the Manawatū, which interested their parents as well. “They were going home talking about whakapapa, and their parents were saying, where did you learn this from? It was way more whakapapa than they ever knew.”

“[The children] were going home talking about whakapapa, and their parents were saying, where did you learn this from? It was way more whakapapa than they ever knew.”

Muaūpoko Tribal Authority board member Marokopa Wiremu-Matakatea

The programme was co-designed by a team including whānau, kaumatua, and others from Muaūpoko with teachers from Levin East School. “We thought, ‘what do our kids need?’ – it was driven that way.” Rump says the iwi authority also negotiated the partnership. “Our role was making sure that our kaumatua and the school were getting all the elements in place to make sure it could be a true partnership.”

“We’re finally getting him to open up to us – fantastic progress!”

The programme also included activities with Horowhenua College, which built on an earlier tuakana/teina initiative trialled between Levin East and the Rangatahi Ora rōpū at the college; and a well-attended Muaūpoko three-day school holiday programme led by Muaūpoko teachers from far and wide.

Rump says that the next programmes being planned by Muaūpoko are likely to include both primary and intermediate schools and focus on maths and technology. The iwi is building a repository of digital resources which can be shared with all eight schools in Taitoko/Levin, and is also hoping to open its own kura.

Some hope that training on cultural responsiveness will expand

However, some Māori and Pasifika children are still experiencing racism at school, which affects their trust in their teachers and impacts negatively on their success, according to the Commissioner for Children. [Office of the Children’s Commissioner, Education Matters to Me: Key Insights, January 2018.]

There is a 10% difference between Māori and non-Māori achievement across many measures, which is one of the causes of New Zealand’s poor ranking by the United Nations on scores related to educational equity. [Stuff, 30 October 2018.]

Our education system is still widely failing to meet the needs of our Māori and Pasifika students, hence the need for change. And there is reason for hope.

Our education system is still widely failing to meet the needs of our Māori and Pasifika students, hence the need for change. And there is reason for hope. This government has recommended in its Child Well-being Strategy, released by Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern and the Minister for Children Tracy Martin: “That children are free from racism, discrimination and stigma.” [Cabinet Paper: Child Well-being Strategy: Scope and Public Engagement Process. p11, point 59.]

Experts in culturally responsive education for Māori, Pasifika and other ethnicities are likely to recommend expansion of culturally responsive teacher training programmes like Te Kotahitanga into the primary and early childhood sectors, as well as secondary.

Before its election, Labour promised to fund “dedicated professional development programmes that have proven success in raising educational achievement for Māori students, such as Te Kotahitanga” and this was supported also by New Zealand First. In 2018 $1 million was budgeted for “strengthening equity and lifting achievement for Māori students” to fund a “design phase which includes bringing together Māori education experts, researchers and education sector leaders to investigate initiatives, like Te Kotahitanga, and evidence of what works well for Māori learners in schools.” [Reply to questions, Robert Johnson, Press Secretary, Office of Kelvin Davis, Associate Minister of Education, 23 October 2018.] This group of specialists has been formed and is chaired by Professor Mere Berryman.

Berryman has a background that spans more than 40 years in primary school teaching and educational research in both Māori and English-medium settings. She was also part of the leadership of Te Kotahitanga from inception and when it was implemented in secondary schools between 2000-2013. From her experiences in education she has clear insights into what professional learning focused on equity might look like across the system. However, primary school leaders and teachers who are unfamiliar with Te Kotahitanga might well question what the programme was, what the outcomes were and how a secondary school intervention might be relevant to primary schools.

What was Te Kotahitanga?

Based out of the University of Waikato, Te Kotahitanga was an iterative research and professional development programme over five phases. The programme drew from kaupapa Māori theory and research undertaken in kura kaupapa Māori and was initially led by Professor Russell Bishop. Te Kotahitanga aimed to improve teaching practice and Māori student engagement in English medium secondary schools.

Researchers began by asking Year 9 and 10 Māori students and others, What would engage them more with learning? The subsequent initiative used what had been learned from these students in the development and implementation of an Effective Teaching Profile.

Te Kotahitanga developers then focused on supporting teachers to examine their values and beliefs and to shift their thinking and pedagogy in order to create more culturally responsive and relational contexts for learning. When contexts such as these were created they found that Māori student engagement increased and subsequently their achievement began to improve.

What were the outcomes?

In Phase 3 and 4 of Te Kotahitanga, about half of the schools increased and sustained successful Māori student outcomes and about half of the schools did not. Te Kotahitanga Phase 5 schools, working with school leaders and a Strategic Change Leadership team, had considerable increases in the number of Māori students who stayed on at school into Year 13, and who achieved more advanced secondary qualifications. An analysis of this data indicated that the number of Māori students who attained UE in Phase 5 schools, for example, was almost double the number of Māori students in the comparison schools. [Alton-Lee, A (2015). Ka Hikitia, A Demonstration Report, Effectiveness of Te Kotahitanga Phase 5, 2010-2012. Iterative Best Evidence Synthesis (BES) Programme, Hei Kete Raukura, Ministry of Education.]

Additionally, Māori students’ experiences of schooling in these schools began to change markedly. In one school they reported that their teachers really knew and cared for them and that they experienced “the opposite of racism”. [Alton-Lee (2015), pp28-29. Comments from William Colenso College.] Unfortunately, despite improving Māori student success across a range of measures, including at all levels of NCEA, Te Kotahitanga was considered too costly, and was discontinued in 2013.

How is Te Kotahitanga relevant to primary school educators?

Disparities between Māori and non-Māori students continue to exist at both primary and secondary school levels and a pedagogical intervention to address this is needed across both settings. Some of the research upon which Te Kotahitanga was based originated in Māori and English medium primary school settings and was led by Berryman.

Since the funding for Te Kotahitanga finished, Berryman has continued to focus on improving equity and lifting Māori student achievement using an accelerated theory of change with schools across all levels of compulsory schooling. She is currently the director of Poutama Pounamu (based with the University of Waikato), which is a team of researchers, expert partners and professional learning and development (PLD) accredited facilitators.

The team has drawn from the findings of Te Kotahitanga and from the research undertaken by the Poutama Pounamu Māori education research centre (in the 1990s) to refine “what works”. Together they have developed a range of responsive, pedagogical support interventions.

Comprising primary and secondary school educators, the Poutama Pounamu team provides specialised teaching and leadership support through centrally funded PLD in the areas of cultural relationships for responsive pedagogy, adaptive expertise, and home, school and community collaborations.

While this learning and support is predominantly delivered through face-to-face contact, Poutama Pounamu also offers an online blended learning course which enables the almost 300 participants to examine education theories, history, policy and research and consider how this plays out or could play out in their practice with Māori students and whānau. Having completed the online modules, participants receive a certificate in Cultural Relationships for Responsive Pedagogy and also have the option of completing a summer school course to attain the equivalent of two Masters level papers. While a comprehensive summary of the evolution of Poutama Pounamu over 20 years of iterative research can be found on their website, in 2018 the team worked in approximately 18 communities of learning/kāhui ako which include ECE centres, and more than 40 individual state and state-integrated schools at primary, intermediate and secondary levels.

Therese Ford, a member of Poutama Pounamu, reports that, “As a team what we are continuing to do is ensure that the kaupapa that started in the original Poutama Pounamu, with kuia and kaumatua, with iwi and hapū, with learning on marae, continues to grow and it gets stronger. We didn’t come out of nowhere, we came from a whakapapa that is grounded in kaupapa Māori theory, critical theory and research.”

The Poutama Pounamu team is excited to be working with teachers, leaders, board of trustee members and whānau across the learning pathway – ECE, primary and secondary schools.

Therese says that the team is excited to be working with teachers, leaders, board of trustee members and whānau across the learning pathway – ECE, primary and secondary schools. Poutama Pounamu is finding that there is an appetite for research-based PLD support that enables educators to recognise and address racism and bias (conscious or unconscious). They are finding it encouraging to see a more determined commitment emerging in schools and kāhui ako that is focused on creating more equitable learning environments that promote belonging and wellbeing for all.

Like the wider education community, Poutama Pounamu awaits the outcomes of the various education wānanga and reviews that were undertaken across the education sector throughout 2018. They want to continue their contribution in the coming years to endeavours that seek to strengthen equity and lift achievement of Māori students. Mauri ora.

Passion and collaboration working

Another initiative working towards inclusiveness for Māori in primary schools is the Māori Achievement Collaboratives (MACs), which are under the umbrella of Te Akatea (the New Zealand Māori Principals’ Association) and work with principals and other leaders to improve cultural understanding and relationships.

This is done through cluster hui and one-to-one korero as well as through both regional and national wānanga on marae.

“That’s our passion, we work with principals. The school won’t change unless the principal does,” says Hoana Pearson, Te Pitau Mātauranga, national co-ordinator of the MACs. Most principals are non-Māori. “Feel the fear, we’ll walk with you, let’s do it. It’s getting people to step out of their comfort zones.”

Te Akatea is the accredited provider organisation for this professional development network and works in association with the New Zealand Principals’ Federation. There are four full-time and two part-time accredited facilitators working as regional MAC co-ordinators. About 12 regional cluster collaboratives involving 175 primary and intermediate schools are involved. There are also a small number of secondary schools.

“We’ve got 43,830 students – out of those 14,972 are Māori, or 34%. And of those, 5883, or 39%, are identified as needing support in their learning,” says Hoana. Data shows a 3–4% improvement in children’s reading and maths and an 11–13% improvement in writing at schools where the principals are working with MACs, she says.

But kura feel neglected

There is no doubt that kura kaupapa Māori and kura-a-iwi lead the field when it comes to surrounding tamariki Māori with a supportive cultural context and working closely with whānau. Many parents know their tamariki are most likely to succeed in this context and are willing to make the commitment required.

There is a shortage of Māori medium teachers and demand for places at kura is outstripping supply.

And yet kura kaupapa feel neglected when it comes to funding and frustrated that they are not being supported to build capacity. There is a shortage of Māori medium teachers and demand for places at kura is outstripping supply – long waiting lists are a problem, as parents wait six to eight months for their child to enter kura, says Rawiri Wright, chief executive of Te Runanga Nui o Ngā Kura Kaupapa Māori.

The Ministry of Education acknowledges the success of kura: “NCEA achievement of Māori people in these settings is consistently on par with all in the school population and significantly higher (15 to 20 percentage points) than for Māori in English-medium settings. Furthermore, research confirms that even children and young people presenting with traditional ‘risk’ factors achieve at levels comparable to other children and young people in Māori-medium education.” [Māori Education Briefing to Incoming Minister, Ministry of Education, November 2017.]

But, the MoE continues: “Despite the exceptional results for Māori in Māori-medium kura, fewer than 19,000 Māori currently attend kura. Furthermore, due to retention issues within the pathway, only a small portion of these Māori remain in kura for the duration of their schooling journey. While there are opportunities to stimulate participation in Māori-medium pathways this in itself will not address the significant Māori education challenges.”

What is the government doing to stimulate participation in Māori medium pathways? There has been a small increase in the number of Māori medium teaching scholarships offered, from 52 in 2017 to 65 in 2018. And work towards a new qualification, Te Kawa Matakura, for secondary students proficient in “te ao Māori” may make a small difference.

But leaders of the kura kaupapa movement say they’re almost “at breaking point” regarding the lack of support for kura. They have already lodged a claim with the Waitangi Tribunal and may take the issue to the United Nations.

Leaders of the kura kaupapa movement say they’re almost “at breaking point” regarding the lack of support for kura.

After meeting with Rawiri Wright and others last month to discuss funding, Associate Education Minister Kelvin Davis has at least agreed to meet “regularly” with Te Rūnanga Nui, which he describes as a “peak body” along with Ngā Kura-a-Iwi, Kohanga Reo and wānanga.

“I’m interested in hearing their views on how we can achieve our shared goal of providing a seamless pathway for Māori learners from early learning right through to tertiary, ” says Davis.

The ministry suggests that mainstream schools also learn from the success of kura: “Insights from its success can be applied elsewhere in the system.” Insights include making tamariki feel safe, included and valued; quality, culturally responsive teaching; and partnerships with whānau, iwi and local Māori communities.

Extra funding for te reo for teachers

Most primary schools offer either no Māori language or merely the basics (“taha Māori”). The government has shown its commitment to boosting teacher knowledge of te reo by promising funding of $11.4 million over the next three years to do so.

Te Ahu o te Reo Māori funding was announced in Budget 2018, and will support early childhood and primary teachers to deliver te reo in classrooms through five initiatives:

- an on-line hub for te reo Māori in education resources

- an event through which te reo Māori will be showcased

- te reo Māori courses designed for teachers

- a teacher network to leverage collaboration as a teaching mechanism

- teacher guidance to support teachers to integrate te reo Māori across the learning environment.

A further $2 million over the next two years has also been allocated to Te Kawa Matakura, to develop a programme and qualification for secondary students who exhibit excellence in te ao Māori. While few details have yet been released, this initiative may support pathways for proficient Māori students into careers in teaching or education.